Domain-specific Language Implementation Patterns (Pt. 1): Writing a DSL from scratch

1. Language application architecture Programming language design is a mental process involving choosing the types of the target language, the paradigms it supports, the operating systems and runtimes it can execute on, and also the grammar of the language. This process is a complex process and ...

1. Language application architecture

Programming language design is a mental process involving choosing the types of the target language, the paradigms it supports, the operating systems and runtimes it can execute on, and also the grammar of the language. This process is a complex process and will affect greatly on the practice of implementation. For example, C# has its own design team, called C# Language Design Team, which holds responsible for making decisions about future C# features. This team needs to work closely with the implementation team and the community to make sure new language features they agreed on are practical.

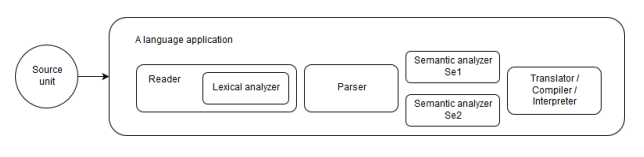

As stated, there have already been many libraries, frameworks, and tools for rapid programming language development. However, they are mostly used for the first phase of language development to reduce repeatability. Most of the hard work divides into all other phases, which takes output of the first phase to process. It is therefore essential to be knowledgeable of how the everything is put together in the first place. Generally speaking, a standard language application such as a compiler application is segregated into multiple phases, each follows the next, each takes output of the previous as input. This whole architecture for building a language is called a multistage pipeline. The input of the pipeline is a piece of text (the source code), the output varies based on the purpose of the application. For language applications such as compilers, the output are usually executable programs, or technically binary code. For other types of applications, like source code analyzers, the output is normally a list of actions that can be performed onto the source code to either modify it, improve it, or format it. Based on the purpose and functionality of the language application, the multistage pipeline‟s structure also varies. Each stage in the pipeline can be considered as a small program, fetching in input and dishing out output for the next program. However inconsistent in the implementation strategies, most pipelines follow some basic ideas. First of all, there is a reader program that reads and recognizes input and construct an intermediate representation (IR). And some analyzer programs perform in-depth analysis on the IR and make modifications if necessary. At the other end of the pipeline there will be a generator program, fed by the analyzers with the IR, a generator will generate the required final and end the pipeline execution.

2. Lexical analyzer

The reader program is often the first program to be executed, and the output of this program determines the implementations of other programs further in the pipeline. In order to recognize the input text, the reader program divides itself into multiple sub-stages, these are small recognizers that match the input text and map it to an IR. These recognizers take in the input of the previous recognizer, and a grammar, to produce necessary output. Although a grammar is not necessarily required, it is a vital tool in helping to realize the rules of the language. A common reader consists of two basic recognizers: a lexer and a parser.

The lexer is a recognizer that identify the substructures of a sentence. A sentence in a programming language is a structured construct that when placed together sequentially, make up a coherent block of code. A sentence can be a statement, for example:

X = 0

The meaning of this sentence is: “we assign value 0 to value holder x”, or in other words, the value of x is now 0. This sentence can be identified by three parts: the value holder x, the operator =, and the value 0. In this instance, each part consists of only one character, but it doesn‟t mean every part has only one character. Each of these parts is called a token. And the recognizer program that reads and processes tokens is called a tokenizer, or lexer, lexical analyzer, scanner. Considering another example:

X = 'a'

This sentence has the same meaning as the last example, but now the value is 'a', denoting a character value. All three symbols make up a single token that the computer can recognize. Writing a simple lexer is easy, a lexer implementation for arithmetic operations in pseudo-code is as follow:

foreach (char in input)

if (char == ['1'..'9'])

tokenize_number()

else if (char == ['+', '-', '*', '/'])

tokenize_operator()

else

tokenize_unknown()

In this simple and opinionated implementation of a lexer program, each symbol fed into the program must not represent more than one meaning, else the program will default to the first option it meets.

Building a lexer manually by hand is repeatable and erroneous. This is the first challenge in writing an implementation for a programming language. It is not a matter of some complex algorithm or calculation, but the first problem is to write a lexer that isn't susceptible to changes, flexible, and future-proof. Each time a new type of token is added or a new rule is introduced, the lexer will have to be modified in a rigorous way and can affect the existing code. Luckily, most lexers are very similar in the implementations despite different language features. In order to obviate this problems, there are tools to automatically generate lexer code. Grammars are used to describe language structures, and so they can also be used to describe lexical rules (rules used by lexers to recognize and enforce correctness on the character level). A grammar that describes some lexical rules may look like this:

ID : ('a'..'z'|'A'..'Z')+

Number : '0'..'9'+

This grammar can be used along with a text input by a lexer to produce a set of tokens. For example, if an input is:

foo 12 bar

A lexer using the previously mentioned grammar will produce this set of tokens:

[ ID(foo) | Number(12) | ID(bar) ]

A visualization of a lexer program which takes in a source unit and produce tokens.

A visualization of a lexer program

(To be continue)